Birds and Flowers of Michigan

Birds and Flowers of Michigan by Iris Eichenberg

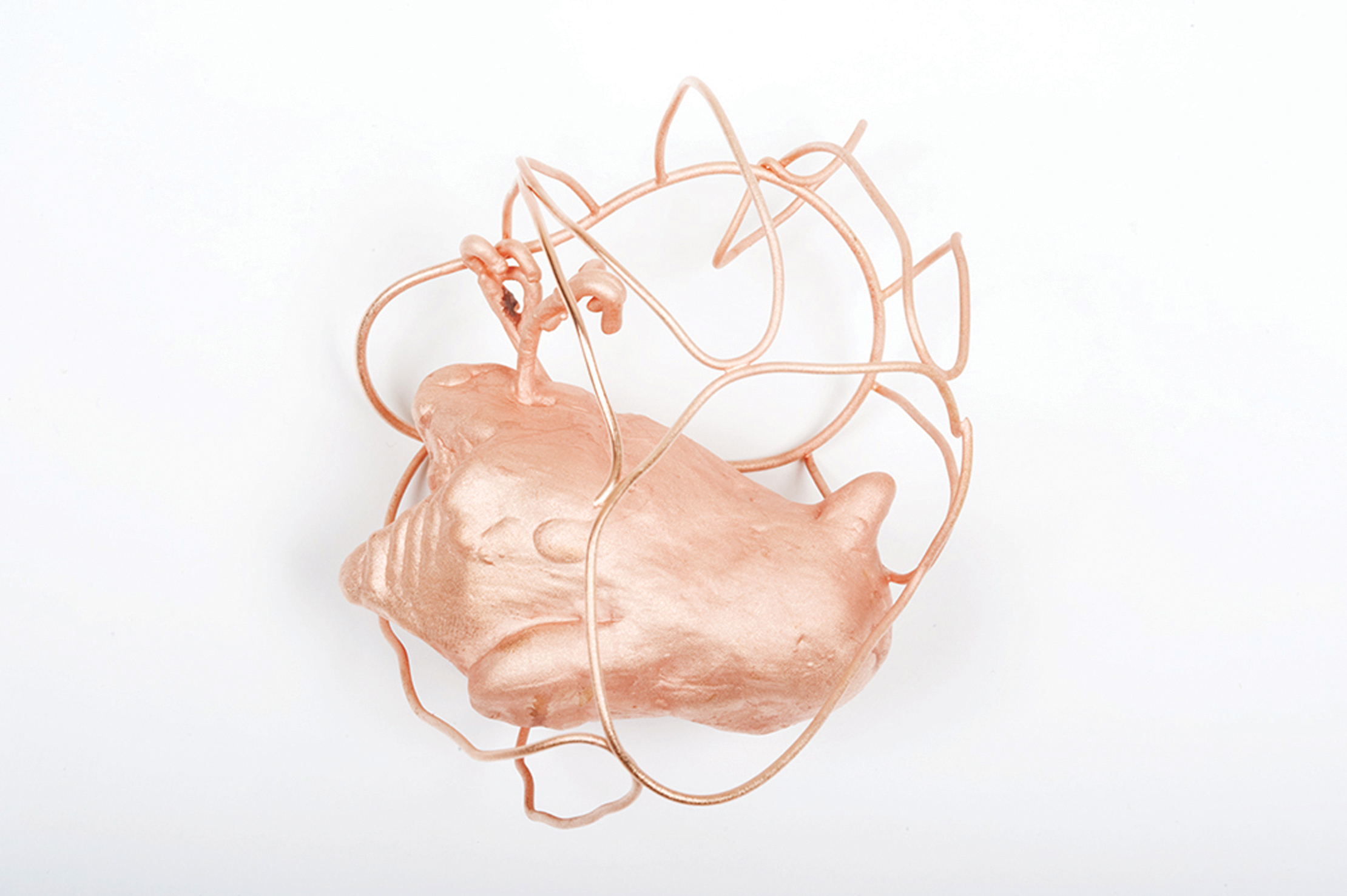

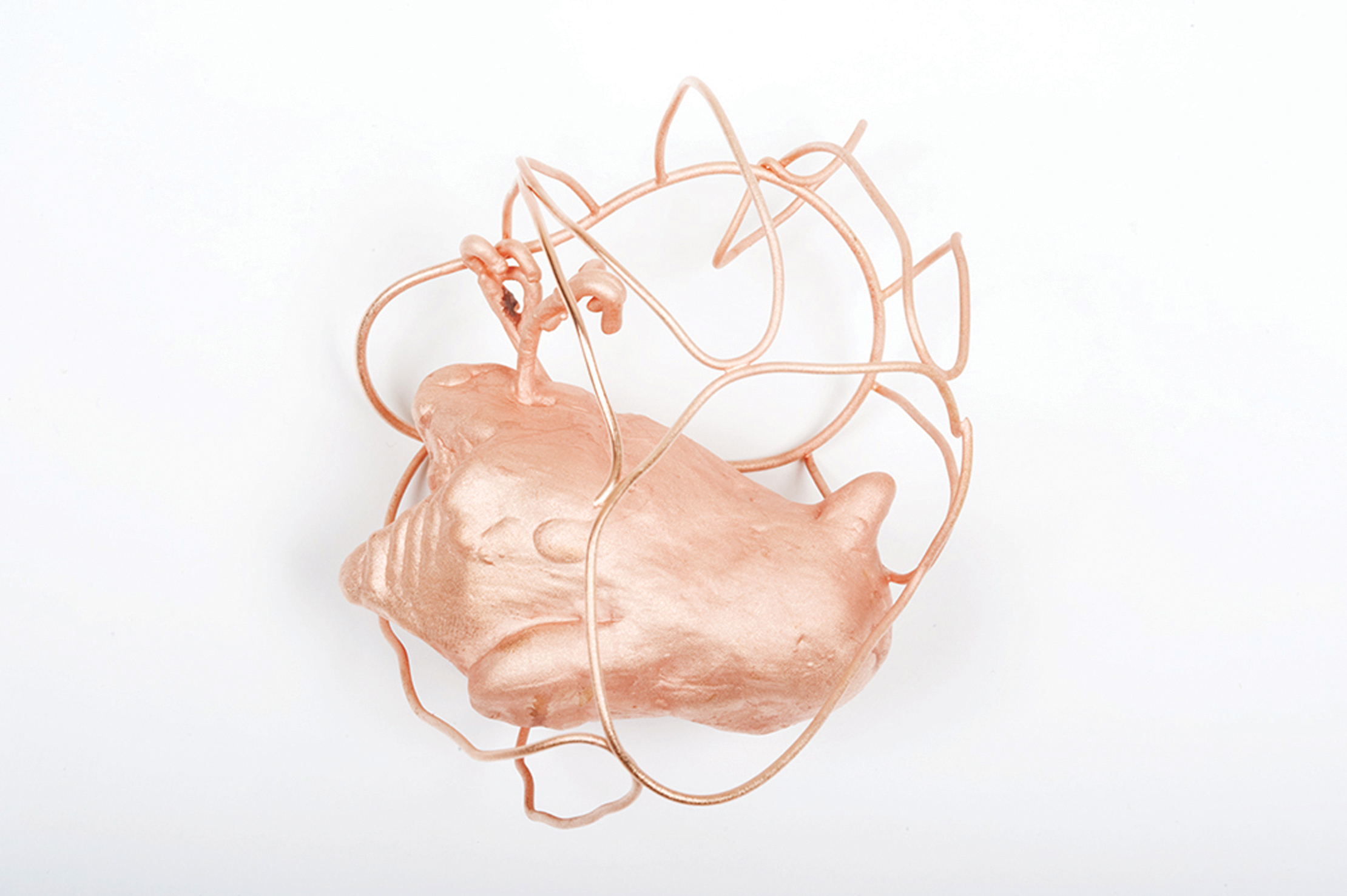

Tongue-in-cheek, and hence self-reflective, or flat to the point of meaninglessness, the title of Iris Eichenberg’s new series of work, Birds and Flowers of Michigan, does little to suggest the intensity of the coupling between these fancifully shaped, (pink) flesh-colored flowers, and the delicate, copper-colored birds, whose dead frames appear at once contained in and uncontainable by their equally broken framing cages. These are highly personal works, as intimate and familiar, and at once as exotic and estranging as life and death are in their coupling in one’s—this one’s and that one’s—everyday existence. The breathing, trembling flesh, materialized in the erotically charged shapes and folds of paradoxically colorless flowers are mounted on silver plates, whose whimsical outlines reinscribe, two-dimensionally, what the three-dimensional depth of the fleshy flower shapes exuberantly celebrate: the irrepressibility of the palpitating heart beating under the skin, the largest bodily organ whose very tenuousness, being no more than a thin membrane between inside and outside, self and other, simultaneously marks the fragility of life, and the unpredictability of the movements of the pumping heart.

The contrast between these deliciously alive, yet also quite repulsively carnal flowers, and the lifeless bodies of the caged birds—some appearing trampled to death, or even trampled upon after being taken out of their element—grounded by captivity, and ultimately, death, could, perhaps, not be starker. Yet, in their all but threadbare symbolism, both birds, in their freedom to take off, to soar, to trace their lines of flight through the sky, as they do the flight of our minds and our imaginations, and flowers, used for centuries in religious and spiritual symbolism, and, since Victorian times, used to represent emotions, to transport feelings of love, commiseration, grief, and desire, are always already more and other than their material shapes and outlines. As such, the flower, rooted and growing in soil, and the bird, reaching for and flying through the sky, jointly frame the life-in-death and the death-in-life principles that mark their own as well as our material and symbolic existence. Perhaps, then, the birds are not so much trapped in, killed by their broken cages, but expressing, in their almost unbearable, lifeless frailty, their entanglement in the at once so intimate, and yet so abstract “thisness” of their concrete existence, as artifacts, the elusive, inescapable coupling of life and death, including our own lives and our own deaths, in the tangled mass of infinite beauty and inevitable ugliness that is actualized existence.

The tension in Birds and Flowers of Michigan does not, as in earlier series of Eichenberg’s work, derive from the clash between seemingly incommensurable materials and unexpected or non-traditional artistic techniques. The carefully sculpted birds and flowers function as archetypical forms, marked by human hand, taking their various shapes in simple materials: the flowers are made of ceramic-like pinkish-grey compound, the birds and their frames consist of gold-plated, electro-formed copper. The myriad variations of lines, their crossings and departures, form three-dimensional drawings whose tension resides in the singularity of an overarching idea, emerging in a tactile awareness, at once trite and almost sublime.

©2010 renée c. hoogland